Writing a Kernel Driver

Intro

I have worked on a few kernel drivers before and every time I spend a couple of days setting up the build environment and figuring out how to do everything again. This is my attempt at helping myself out in the future. So to future Dave, you owe me a beer.

A kernel module is a binary that can be loaded into the kernel at runtime and extends the kernel’s functionality. A driver is a specific type of kernel module with the intended purpose of bridging a device to some subsystem in the kernel. This subsystem can be a file like interface, video output or audio. An example would be a PCIE card that has an HDMI port, the driver must translate the raw video output to format the is understood by the PCIE device.

There are a lot of different types of drivers, this article is aimed at creating one with a file interface for a hardware device. Basically it facilitates userland access with a device using both file operations and sysfs. Because most programming language have some mechanism of interacting with files a file interface is very powerful and easiest to use. There are a lot of other types of drivers and, perhaps in the future, the git repo can be branched to accomodate these variants.

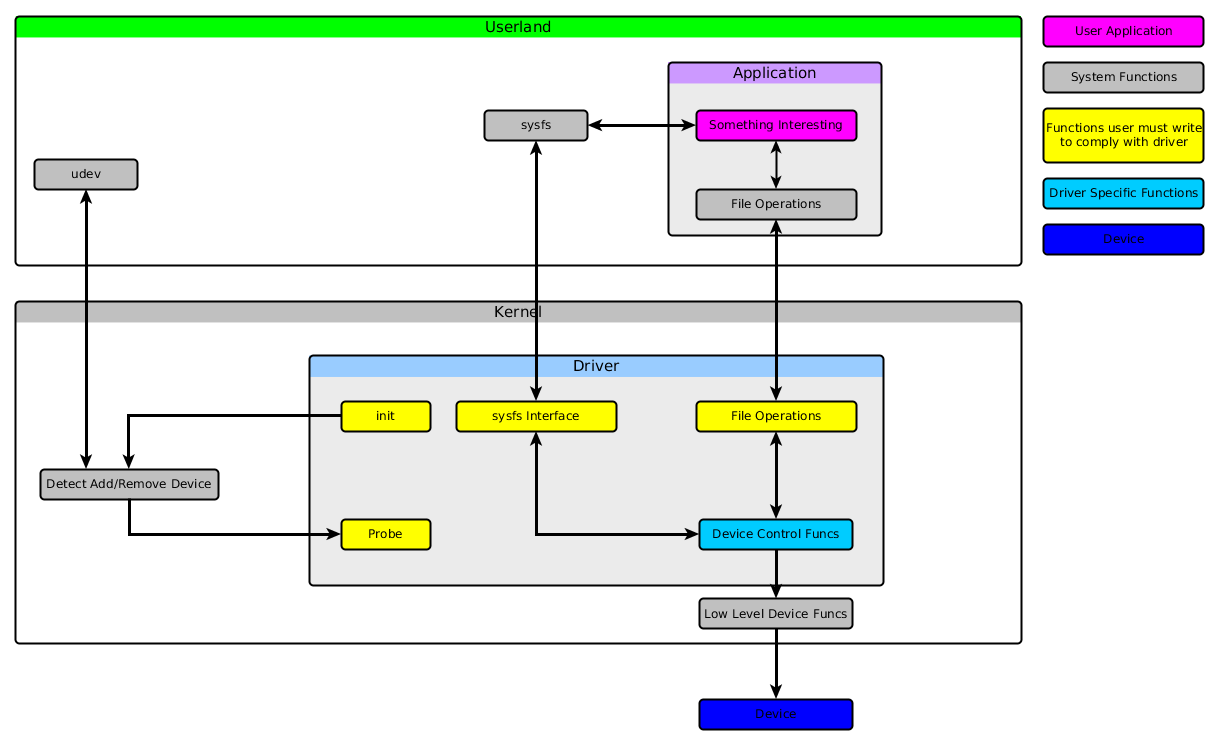

A high level view of how the kernel, driver, device and user applications interact with each other:

This guide will walk through:

- Setup The initial setup when building a module include preparing the host and downloading the code.

- Design The design of the module

- Code-Build-Debug-Repeat Debugging

To make things easy for this guide I’ll declare the following things:

- Module Name: wallaby

- Module Location: ~/Projects/wallaby

Setup

The one time setup consists of the following steps:

- Setting up the system

- Cloning the github repo

- Rename the module

System Setup

Setup Ubuntu to build the kernel module. We’ll need both build-essentials and the kernel headers.

sudo apt-get install linux-headers-$(uname -r)) build-essentialsGetting the skeleton

I created a skeleton that can help get started with the build process

Clone this repository to somewhere on your system.

git clone https://github.com/CospanDesign/kernel-module.git wallabyModifying the Skeleton with your module name

There is a script that needs to be run one time that will rename the modules and all references to that module. It should probably be deleted after it’s use or you may inadvertently rename things later on.

Design: Anatomy of a driver

A driver can be broken down into four regions.

- Module Initialization/Remove.

- Per Device Identification, Initialization and Removal.

- User Interface.

- General Driver Infrastructure.

ioctrl vs sysfs

As stated in the intro this is one type of driver focused on presenting a file like interface to a hardware device. File interfaces are useful becaues most programming languages can interact with files. There is one issue. Sometimes we need to interact with our hardware in a way that doesn’t make sense using the stnadard file operations like ‘read’ or ‘write’. For example in order to configure a UART to operate at a specific baudrate users would need to use ‘out of band’ signals that communicate with the device outside of the standard data flow.

‘out of band’ signaling has changed from ioctl to sysfs. If you have ever used ioctl you can appreciate that it was frustrating to say the least. The main reason for this is because, if you wish to use and ‘out of band’ signal. the user needed to know what specific ioctl corresponded to what function as well as what values to read/write were valid. The problem was exhaserbated by the fact that an ioctl for one driver could be completely different for another driver. As can be imagined there were great attempts to find an elegant solution using things like known ioctl numbers.

A newer approach to controlling devices, drivers and general system functionality was introduced with sysfs. There are a lot of resources on the web describing the history and benefits of sysfs including this great paper but suffice to say we will be using sysfs to configure our device.

Kernel Module Installation and Removal

When a driver is loaded and removed the kernel uses the ‘module_init’ and ‘module_exit’ macros to identify which functions should be called. driver developers can assign a specific function as follows:

static int wallaby_init(void)

{

}

static int wallaby_exit(void)

{

}

module_init ("wallaby_init");

modue_exit ("wallaby_exit");The responsibility of these two functions are as follows:

- init

- Perform one time configuration for the driver.

- Describe how the kernel can identify the device.

- Request character device region.

- exit

- Remove and cleanup any resources the driver declared.

- Release the character device region

Recognizing a Device

A driver can be installed but it may not do anything until an associated hardware device is connected to the computer. The driver needs to tell the kernel how to recognized the device. Recognizing a device is dependent on protocol.

For example, all USB devices contain a descriptor that the host computer can read. This descriptor contains, among other things, two identification numbers:

- Vendor ID: A 16-bit unique vendor identification number.

- Product ID: A 16-bit unique ID that distinguish one vendor product from another.

The kernel contains infrastructure to detect vendor and product IDs. This makes the process of identifying drivers much easier. The module must register the IDs of interest to the kernel. When the kernel detects these IDs the kernel will call the modules ‘probe’ function. When the device is removed the kernel will also call the ‘disconnect’ function.

I like to think of the kernel managing a construction yard. A driver registers or tells the kernel that they can drive specific vehicles and can identify these vehicles using provided ID. If a vehicle matching any of the provided IDs are found the kernel will then notify the driver that there is a valid vehicle by calling the drivers ‘probe’ funcition. Similarly if the vehicle is disconnect the kernel will notify the driver by calling the ‘disconnect’ function

The ‘probe’ and ‘disconnect’ functions are not declared using a macro instead the driver usually declares these two functions in a protocol specific way. For example, USB uses a structure called usb_driver that is populated by the driver author and may be augmented by the module’s ‘init’ function.

The structure is populated with usb specific functions. a great reference to use is the ‘usb-skeleton.c’ driver found in kernel/driver/usb folder. Here is an excerpt showing the ‘static struct usb_driver’ and the ‘probe’ and ‘disconnect’ functions that are called when a recognized device is inserted and removed.

#define MODNAME "skeleton"

static int skel_probe(struct usb_interface *interface, const struct usb_device_id *id)

{

//The kernel calls this function when the vendor and product IDs registered with the kernel are detected.

return 0;

}

static void skel_disconnect(struct usb_interface *interface)

{

}

static struct usb_driver skel_driver = {

.name = MODNAME,

.probe = skel_probe,

.disconnect = skel_disconnect,

.suspend = skel_suspend,

.resume = skel_resume,

.pre_reset = skel_pre_reset,

.post_reset = skel_post_reset,

.id_table = skel_table,

.supports_autosuspend = 1,

};

module_usb_driver(skel_driver);The full module can be found here: ‘usb-skeleton.c

Here is another example of the PCIE driver:

#define MODNAME "skeleton"

static int skel_probe(struct pci_dev *pdev, const struct pci_device_id *id)

{

return 0;

}

static void pcidriver_remove(struct pci_dev *pdev)

{

}

static struct pci_driver skel_driver = {

.name = MODNAME,

.id_table = skel_ids,

.probe = skel_probe,

.remove = skel_remove,

};Reserving space for character devices

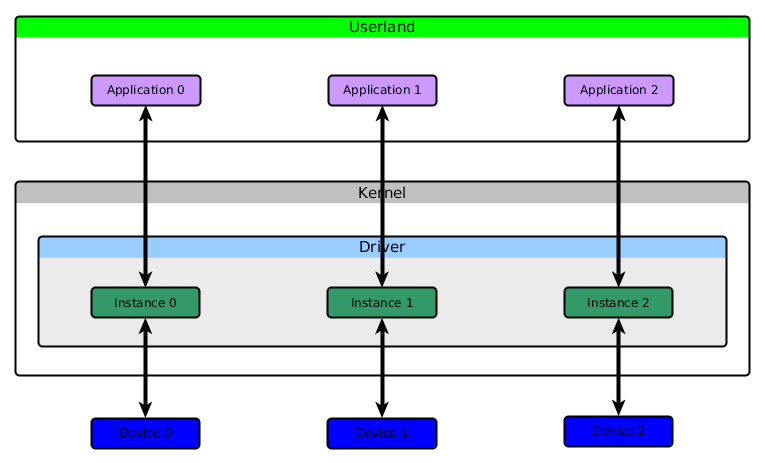

Because we want to interact with our driver using a character devices files we need to ask the kernel to reserve some space for all the possible devices we will be using. Then, if a device is detected, we can associate a character device file with it. Because multiple devices can interface with a single module there needs to be a way to distinguish one device from another.

In the past this was accomplished using strict major and minor number identification. As an example virtual consoles and serial terminals have a major number of ‘4’ and when you wanted to declare a new unique tty device you used the major number ‘4’ and took a minor number.

You can view character devices in the /dev directory and see which major and minor number are currently in use.

cd /dev

ls -l

...

#Excerpt

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 0 Apr 16 13:46 tty0

crw-rw---- 1 root tty 4, 1 Apr 19 07:16 tty1

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 10 Apr 16 13:46 tty10

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 11 Apr 16 13:46 tty11

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 12 Apr 16 13:46 tty12

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 13 Apr 16 13:46 tty13

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 14 Apr 16 13:46 tty14

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 15 Apr 16 13:46 tty15

...In modern drivers the module developer does not declare explicitly which major or minor number they want to use, instead the kernel will decide, In order to reserve some character device files of our own we would make our request within the init function.

int alloc_chrdev_region(dev_t *dev, unsigned int firstminor,

unsigned int count, char *name);Parameters:

- firstminor: first minor number you wish to use for the driver (Usually 0)

- count: The number of consecutive minor numbers you want

- name: The name of the driver

- dev: The first major/minor number generated.

To remove the device file use this function:

void unregister_chrdev_region(dev_t first, unsigned int count);Parameters:

- first: The first major/minor number you received

- count: The number of consecutives device structures.

Class Instantiation

In order to interface with the sysfs we need to instantiate a class

Per Device Probe/Disconnect

Although there may be only one kernel module there may be multiple devices that can work with that driver. The probe function is called when a new, unique, device is attached. The distinction between driver and unique device instances is illustrated:

Interfacing with your driver

From the kernel’s point of view the driver presents a recognized interface to a device. From the device’s point of view the driver translates the generic requests such as ‘read’ and ‘write’ to a device specific native language.

The term recognized interface can mean many different things. One interpretation can mean a file like interface. Where the driver enables the user to interact the device in the same way they would interact with a file. Files allow the user to ‘read’ and ‘write’, some allow you to ‘seek’. Most programming languages understand how to interact with a file so presenting your driver as a file allows users to interface with the device in an easy to use way.

Drivers do not need to interface with the user directly, instead the kernel may attach the driver to another module. As an example a USB camera may not interface with the user directly through a file but instead interface with a ‘video4linux’ module that transates data from the driver to the video subsystem.

File Interface

We will use a file interface to communicate with the driver. As stated above most programming languages understand how to interact with a file. One issue with file interface is out of band signals or signals that are not specifically for reading and writing to a device may not be easy to do. We’ll use sysfs in a later section. For now we’ll talk about how to implement the file operations.

File oeprations is accomplished by:

- Declaring a file_operation structure that points to appropriate signals.

- Instantiated an ‘inode’ or a file like entry into the /dev directory.

Declaring a ‘file_operation’ Structure

Inside the driver we’ll include the file operation structure and populate it with functions that satisfy the required functionality.

//-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

// File Operations

//-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

int wallaby_open(struct inode *inode, struct file *filp)

{

return SUCCESS;

}

int wallaby_release(struct indoe *inode, struct file *filp)

{

return SUCCESS;

}

ssize_t wallaby_write(struct file *filp, const char *buf, size_t count, loff_t = SUCCESS)

{

return 0;

}

ssize_t wallaby_read(struct file *filp, char * buf, size_t count, loff_t *f_pos)

{

return 0;

}

struct file_operations nysa_pcie_fops = {

owner: THIS_MODULE,

read: wallaby_read,

write: wallaby_write,

open: wallaby_open,

release: wallaby_release

}There are more file operations to use but these are the minimum (I could tell). If you would like to implement more of the file\operations you can look them up here:

Declaring sysfs interface

As discussed above sysfs is the modern place where out of band signals can be implemented. Because sysfs exposes named interfaces users can more easily determine what the different signals mean.

There is a much better explanation of sysfs here:

For brevity I’ll only give a quick example of how to read and write values to/from the driver:

First create an attribute structure:

const char wallaby_name[] = "attr1";

ssize_t show_wallaby_attr1 (struct device *dev, const char * buf){

printk("User show: %s\n", wallaby_name);

buf = wallaby_name;

return 0;

}

ssize_t store_wallaby_attr1 (struct device * dev, char * buf, size_t count){

struct attribute* wallaby_attr = dev->user->attr1;

printk("User set: %s\n", buf);

return 0;

}

/* Start Create */

int retval = 0;

//Create

struct attribute* wallaby_attr = (*struct attribute) kmalloc(sizeof(struct attribute));

struct device_attribute *wallaby_dev_attr = (*struct device_attribue) kmalloc(sizeof(struct device_attribute));

wallaby_attr->name = &wallaby_name;

wallaby_attr->owner = THIS_MODULE;

wallaby_attr->mode = 666; //Read and write

wallaby_dev_attr->attr = wallaby_attr;

retval = sysfs_create_file(/*Object */, &wallaby_dev_attr);

if (retval) {

printk ("Failed to create sysfs file for attrubute: %s\n", wallaby_name);

}

/* End Create */

/* Start Tear Down */

//Tear down

sysfs_remove_file(/*Object*/, &wallaby_dev_attr);

/* End Tear Down */Code-Build-Debug-Repeat

Now that all the configuration is done it’s time build and test your code

Acknowledgments

I need to pay my respects to the various resources I used to write this post including:

- A nice kernel PCIE FPGA kernel module on github: FPGA PCIE Driver